Gentrification is Changing the Culture of Washington, DC

Washington, D.C., (December 12, 2019), The Metro PCS store on the corner of Florida and Georgia Ave. at the center of the #DontMuteDC conflict.

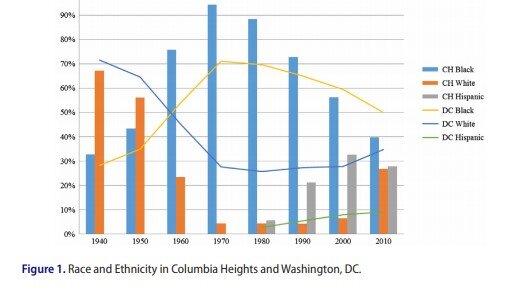

Once referred to as “Chocolate City”, Washington, D.C. was the first U.S. city with a predominantly Black population, touting a demographic of over 50 percent Black. The decades to follow, the Black population would peak at 70 percent. The population held steady throughout the 1980’s with a minor decline in the 90’s. As of 2019, the Black population has dropped below 50 percent, the lowest percentage in six decades. Many blame gentrification for this decline. According to a study highlighted by the Washington Post, D.C. has had the highest intensity of gentrification over a 13-year span.

Gentrification is said to be a process of conforming to an upper-class way of life, or changing a neighborhood to appeal to those with richer tastes. However, the g-word elicits apprehension that minorities will lose their homes and public housing will be demolished while Starbucks and Aldi’s pop up on street corners. Although neighborhood improvements are welcomed by most residents, others fear the shifting demographic, displacement of minorities and the potential loss of culture. Many of the community changes have been made without discussion or input from native Washington residents.

While there is a basic understanding of how gentrification works and how people lose homes in addition to property, there has not been much attention given to how gentrification impacts culture due to the displacement of subsets of people with rich cultural history in a given area. African Americans in Washington, D.C. have a specific genre of music (Go-Go), specific recipes and arts that are not found outside of Washington, D.C. Since the start of gentrification, the venues where Go-Go music were played have been closed or repurposed for different use. Artwork that served as landmarks are being removed and open markets have been closed to make way for chain restaurants and stores. Additionally, the historical pillars of the African American community are not respected by the new residents because they are unaware of the historical significance.

Some argue that gentrification is a good thing as it brings new job opportunities, better housing, and shopping options. The arrival of new developments and increasing property values come at the cost of a reduction in affordable housing for low-income families. In an essay written by professor of sociology, Sharon Zukin, Zukin states “Other studies, including mine, have documented the nearly universal strategy of aesthetic upscaling that produces commercial gentrification and results in displacement of longtime businesses by those that cater to higher-income groups.” This would suggest that the newer businesses and community improvements are not constructed with the neighborhood’s native residents in mind and further propel the erasure of the African American community in the nation’s capital.

Washington, D.C. (August, 2019) Historian and Howard University alum Ebonee Davis purchased her first home in Washington, D.C. in 2011. She grew up in and around D.C. and attended church in the Trinidad neighborhood. When asked if she believed the improvements in the city were made with consideration to D.C. natives, she responded with a resounding no. “Not in terms of benefitting them, not directly benefitting them or intentionally benefitting them. If they happened to benefit, then yes that’s a good thing but I don’t think any of the changes that were made are to intentionally serve people who have been living here for the last two generations.”

There’s also a perceived notion that gentrification has a positive impact on crime rates. This belief is a fallacy. As described in Jana Phorelsky’s article for Harvard, “While additional police presence may seem benign for White residents, it can mean an increased threat for people of color who experience police misconduct and violence at significantly higher rates.” Additionally, there’s more of a vested interest to protect neighborhoods increasing in financial wealth than neighborhoods that are viewed as slums.

“If you’ve got the money, you can make the rules.”

Affordable Housing

“They’ll always have a place to go back to while some of us don’t.”

As D.C.’s demographic rapidly changes, the strain of increased property values is a financial blow felt by many minorities. Retirees on fixed incomes rely on a set budget to cover their expenses. The effects are also felt by low-income families who survive paycheck to paycheck. As many federal housing developments are demolished to make way for mixed-income units, affordable housing is even more difficult to obtain.

Mixed-income housing does not always mean affordable and in some instances, there is no unit for unit replacement for the homes that were torn down. In these cases, residents are displaced and are unable to return to the new developments as there are simply not enough low-income units.

Neighborhoods that once thrived with people of color are bought at a low cost by developers. The remaining citizens of that community are either bought out or forced out of their homes. High rise condos and new homes that are more expensive than the average citizen can afford are then built, increasing property value, rent and property taxes. Low-income and middle-class families that cannot afford the increased prices are forced out of the community, never to return.

In 2015, writer John Butin attempted to discredit the negatives of gentrification on the popular website Slate.com. John labeled gentrification as “rare” and as a “myth”. “As for displacement,” John states, “there’s actually very little evidence it happens.” John’s opinion piece is misleading and it cherry-picks data to downplay the impact of gentrification on minority communities. Yes, gentrification rates are low nationally, yet rates have greatly accelerated in many major cities over the past decade. According to a study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition, 40% of Washington, D.C.’s low-income neighborhoods experienced gentrification between 2000 and 2013. According to the same study, coastal cities had the largest number of gentrified neighborhoods in the last decade. Another study conducted by the University of Minnesota Law School titled “American Neighborhood Change in the 21st Century”, also confirms that Washington, D.C. has experienced the worst gentrification of all major cities since the year 2000.

(More articles on John Butin’s opinion piece here and here.)

Unfortunately, for the low-income families of Barry Farms, Lincoln Heights, and the other 20,000 Black residents that have left the District of Columbia in the past decade, the negative impact is no myth. The demolition of Temple Courts is a key indicator that gentrification is very real.

Temple Courts apartments were low-income homes that were affected by urban renewal in 2008. Temple Courts was part of a redevelopment project called the New Communities Initiative. The initiative was intended to revitalize rundown subsidized housing and increase mixed-income communities in the district. Residents were promised redevelopment without displacement. The original goal was to have residents move into mixed-income homes, while the old subsidized housing was torn down to make way for more new buildings. The project was underfunded and reached a nine-year slump with only 200 units built of the 1,300 units promised. The project was stalled until its reintroduction in 2014.

For residents of Temple Courts Apartments, the reintroduction and overhaul of the program came too late. The apartment complex was demolished in 2008. Displaced families were assured that they could return to the community once construction on a new housing complex was completed. The construction of the mixed-income development never happened. What was built were luxury apartments where 70 percent of the units are sold at market rate while only 59 units were actual replacements for the original Temple Courts residents.

An almost similar fate befell Arthur Capper housing. In 2007, 707 households were displaced when the city demolished the development. A senior building housing 162 units has been constructed since the demolition, but the rest of the 545 displaced families waited close to a decade for the promised redevelopment. The new mixed-income development opened in December of 2016.

School Psychologist, Monica Moment, works with students at Banneker High School and Washington Metropolitan High School.

Ms. Moment has experienced segregation, integration and now gentrification. She was also once a longtime resident of Washington, D.C. moving to the area in 1983 from the South. When she moved to Washington, D.C. she noted that it was her first time living among so many African Americans who also owned businesses in their communities. Ms. Moment shared that in her experience, gentrification impacts the students she works with “socially, emotionally and psychologically.” She goes on to state that currently, “the types of books that they’re reading does not fully represent who they are. The type of history that they are receiving does not match African American history. We are preparing our children to acculturate.”

Popular radio personality and native Washingtonian, “Aladdin Da Prince” has also watched Washington, D.C. change over the years. With a degree in Broadcast Journalism, he understands how imperative it is to preserve history and truth. When asked about the importance of preserving culture he responded, “With culture comes history, comes stories, comes a sense of knowing, a sense of self and when you change that, you also change the narrative of the people.”

(Source Kathryn Howell, Housing Studies 2016)

In a study conducted by Justin T. Maher, Assistant Dean for Graduate Student Success at the University of Massachusetts, the tension between old and new residents of Columbia Heights was highlighted. Maher interviewed a several residents both new and senior to the community. In one interview, a resident describes her experience with newcomers, “In addition to naming newcomers’ class and racial privilege, Valerie also identified newcomers’ failure to communicate with her or treat her with respect. As someone who has lived in the neighborhood all her life, Valerie saw newcomers’ disrespectful attitudes as an insult to her and to other longtime residents similarly invested in fostering a strong sense of community within Columbia Heights.” Maher goes on to explain, “Newcomers revealed continued anxiety about low-income residents of color and longtime residents voiced frustration at incoming residents’ lack of respect.”

As Ron Daniels highlighted in Africology: The Journal of Pan African Studies vol. 12, no.7, “some newcomers are not content to become a part of the community; they arrogantly attempt to change the rhythms, culture and character of the community. For decades it has been a well-established and accepted custom that scores of drummers gather on a designated date at a regular time in Marcus Garvey Park in Harlem to play African music. But, once a large number of “invaders” became occupants of a nearby apartment building, they began to complain to the police and petitioned local elected officials, seeking to ban this longstanding weekly ritual.” Thus calling the police on minorities has become an act of violence of sorts and a clear statement that migrants have no desire to embrace the long-standing culture and instead, plan to oppose it.

The most current examples cultural clashes were displayed over the summer of 2019 when new residents of the Shaw neighborhood quarreled with native Washingtonians and Howard University students. In early April 2019, residents of the Shay luxury apartments complained to T-Mobile about the booming go-go music played at the Metro PCS on the corner of Seventh Street and Florida Avenue. The Metro PCS is directly across from the newly built high rise apartments. The store front had become a Florida Avenue landmark as it has played go-go music from outside speakers since 1995. The hashtag #DontMuteDC was born and a petition soon followed to have the store’s music revived. The decision to “mute” the music was overturned and the music can still be heard by passersby.

Howard University (December 12, 2019), the location where students and new residents clashed over campus grounds being used for public leisure.

Shortly after the music complaint against Metro PCS made headlines, Howard University found itself in the center of a cultural dispute. Students observed new residents walking their dogs on campus and using the campus lawn as a dog park. Students have had confrontations with nearby residents as they push for reverence of Black spaces. One resident pushed back in frustration. Sean Grubbs-Robishaw stated, “They’re in D.C. so they have to work within D.C. If they don’t want to be within D.C. then move the campus.” Grubbs-Robishaw is not alone in his lack of concern for culturally significant spaces. The underlying tension has been brewing in the city for some time.

Bohemian Caverns (December 12, 2019), the historic music venue located in what was once known as Black Broadway, shut its doors in 2016.

Another example of the impact of gentrification on culture in D.C. is the loss of historic sites. Places like Bohemian Caverns where D.C. culture and music thrived. Bohemian Caverns operated off and on as a nightclub in a historic strip of D.C. once labeled Black Broadway. Originally known as Crystal Caverns, the location was operated as a speakeasy during prohibition. Popular for its cave-like atmosphere, musical legends like Miles Davis, John Coltrane and Duke Ellington frequented the popular venue. In 2016 due to financial reasons, the nightclub closed its doors for good, taking along with it a piece of D.C. legacy. The spot was recently purchased and is slated to be re-opened as a Latin bar.

Sankofa Cafe (December 12, 2019), the neighborhood staple has been finding difficulty keeping it’s doors open due to rising property taxes.

The Sankofa Café faces the same plight as Bohemian Caverns. As gentrification increases the cost of living in D.C., property taxes are also increased. Sankofa Café is a staple bookstore in the heart of Howard University’s campus. The bookstore opened in 1997 and has become an integral fixture in the community for not only students but residents alike. Sankofa owners are seeking 10-year property tax abatement from the city council. So far this type of tax break has not been seen for small neighborhood businesses.

Another historically Black neighborhood to see the impact of gentrification is the H Street corridor. A neighborhood that was once a bustling commercial area for African Americans saw a moderate decline after the riots following the assassination of Marin Luther King Jr. For decades, H Street sat dilapidated and drug infested until middle-income professionals began to show interest in the neighborhood. Unfortunately, this neighborhood has seen its share of cultural clashes as well.

Copycat Co. (December 12, 2019), venue at the heart of the most recent cultural clash in the city.

Take for instance the confrontation between a bartender and patron at the Copcat Co. bar in the fall of 2019. The bartender who was African American aggressively approached an African American female patron demanding she leave. The bartender yelled expletives at the patron while other customers watched in shock. The patron left but other customers raised concern to the owner, Devin Gong, about the incident. Devin initially dismissed the actions of the bartender and expressed no remorse that such an incident occurred in his establishment. As the occurrence made headlines, many natives argued that new business owners lack respect for native Washingtonians who are Black. However, the owner of Copycat D.C. countered the argument stating that he is also a minority as he is Asian and therefore, cannot be racist. A few weeks later he fired the bartender involved in the incident citing that “as a company that’s not what we’re about.”

Gentrification is more than trendy coffee shops, bike lanes and boutique grocery stores. Gentrification is also about more than the displacement of members of a given community. At its core, gentrification is about the erasure of a people and the destruction of community ties. When communities are destroyed displacing its residents into neighboring communities or even neighboring states, the culture and history of those communities are lost along with its people. A city that was built off the backs of its minority population should work to be inclusive of all its residents. Washington, D.C. has a responsibility to protect its residents and the culture of the people that make the city so colorful.

Follow me on all social media platforms for updates on this project. Additionally, help me keep track of news stories related to gentrification in D.C. by following my Pinterest board below and sharing newsworthy information with me along the way.